Lunch in Palestine

I first met Ghassan among the coils of cigarette smoke and the clink of journalists’ camera equipment in the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem. He raised his frosted beer glass toward me, above his head in greeting.

‘My friend, you drink with me!’ He rapped his copper table. ‘Tonight we musht drunky!’

This time Ghassan invited me to have lunch at his house on the outskirts of Jerusalem, in Bethany, near a church founded by a Crusader queen to commemorate the anointing of Christ’s feet. A triple-storeyed box of curd-white limestone towered over the olive groves and an elderly man waved from an iron balustrade.

‘I share the house with my family,’ said Ghassan.

‘I share the house with my family,’ said Ghassan.

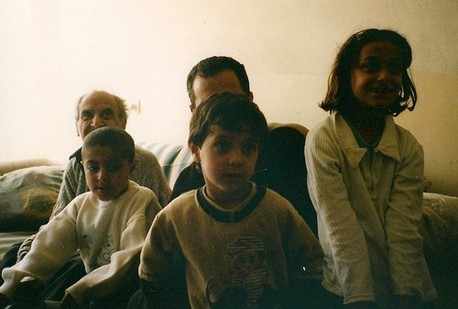

And so it proved, as three generations emerged from the orchard to offer their greetings.

First came Ghassan’s mother and three veiled sisters, whose religious beliefs prevented them from shaking my hand. Then, as we stepped on to a stone-paved forecourt, I met the younger generation. ‘Pick!’ commanded Ibrahim, not so much an eleven-year-old as a mischievous smirk with arms and legs. A wooden ladder moaned as I rested it against an olive tree. Then something pricked my head. Olives rained down on me, trickling off my shoulders and falling into the hijab folds of the veiled sisters who crawled across the forecourt. Between the silver arrowheads of the leaves, Ibrahim’s eyes shone impishly. And on the other side of the tree, too. And on the – hang on! – there were four of them, an army of assailants to whom the tree was a climbing-frame and I – the one they addressed with orders of ‘How Are You!’ – the target of their artillery. Bruised and beaten, I sank into the warm embrace of a sofa, where I became the focus of a more benevolent siege. Offers of cushions, coffee and cigarettes were catapulted by Ghassan and his father, whose whiskers drew the letter W around his shining nose.

‘He fought under the British – with Glubb Pasha,’ said Ghassan.

‘I also fought in ’48,’ snapped his father, smoothing down his gelabiyya. ‘We did not lose Jerusalem in ’48. They lost her in ’67.’

Ghassan’s dark-eyed wife, Amina, laid an enormous dish on a glass-topped table and, picking a grain of rice off her wool-knit sweater, invited everyone to start.

‘This is mensaf,’ she explained, ‘our traditional dish.’

Ripe lumps of lamb bouldered a mountain of rice where almonds and lentils peeked out like scree. I stabbed at my helping with the only available utensil – a spoon – but was quickly corrected.

‘Use your hands,’ snapped Ibrahim Sr. ‘You wash them later.’

The meat dribbled over my self-conscious fingers, while Ghassan’s children surrounded me with loudly munching jaws and wide, astonished eyes.

‘You like the way we live?’ asked Ghassan.

‘Of course,’ I said, eager to please. ‘The Arab world is famous for its hospitality.’

Amina sneered: ‘Sometimes this is a problem. You heard about Hatim?’

‘Oh yes,’ said Ibrahim Sr, ‘you will tell him about Hatim.’

‘He was a Bedouin,’ said Amina, who clearly had every intention of doing so, ‘and he had only one horse, because all the others he gave to his guests. He believed that if anyone came near his tent, he must offer them some food, so now he had only a little left. But his enemy came near the tent, and he prayed to Allah, “Please, please, do not let him pass my tent.” But his enemy walked past, and Hatim looked at the horse and said to himself, “What should I do?” But he knew what was his obligation. So he ran out of the tent and fell on his knees and said to his enemy, “Please, you must come and eat.” And he gave his enemy his last horse.’

Ghassan shook his head. ‘A foolish man.’

‘It is a principle,’ his wife retorted.

‘And a good story,’ said Ibrahim Sr. ‘You will have some more – you are a skinny boy!’

I was already stuffed. But something in his face, as formal as a figure in a Persian miniature, suggested that he was not one of Glubb Pasha’s weaker underlings. A second helping slipped down my gullet, a third followed swiftly behind, succeeded by the morsels of a fourth, so that by the time we sank on puffy sofa-chairs in front of the TV my ribs were being suffocated and there was barely any air-space left in my windpipe.

Despite the images of Pokemon on the TV, and the giggles of the children sitting cross-legged inches from the screen, the atmosphere had turned sombre.

Despite the images of Pokemon on the TV, and the giggles of the children sitting cross-legged inches from the screen, the atmosphere had turned sombre.

‘You know,’ sighed Ghassan, ‘I don’t think I have enjoyed one happy day in Palestine.’

He remembered his days as a student in San Francisco, where he’d driven a Buick and had the pick of the girls.

‘Would you rather go back there?’ I asked.

‘How can I?’ He watched his wife carry an enormous gilt-brass cafetière. ‘I belong in Falasteen.’

He pressed the remote control and Pokemon was replaced by the local news. A woman, her black hijab perfectly suited to widows’ weeds, spidered her arms over her husband’s bier. Amina shook her head at the screen and tilted the cafetière over a cup.